Why JSON Schema? #

The most basic reason for defining a schema is to created a shared understanding of what is considered acceptable between two systems. If I am calling an API or making a remote procedure call (RPC) then it saves everyone a whole lot of hassle if we agree on what the remote system is equipped to handle.

An aside on Data vs. API #

To be crystal clear I am not talking about an API definition here. In that case I’d probably be writing about OpenAPI which is governed by the OpenAPI Initiative. That is about building APIs in a schema-first way.

Since I am primarily concerned with a data schema and am not the API used to work with that data schema, then Open API is just not the right tool.

Think about Microsoft Excel files.

I don’t need to specify how the application (Open Office or Microsoft Excel or Apple Numbers) will consume via their own internal ‘API’. But I do care deeply that the data structure of the Excel file format is extremely well documented and consistent.

What-not-how is a helpful way—for me at least—to decide when to use OpenAPI (how and what) vs. JSON Schema (just what).

That’s what I am working on right now: more of a file format or standard data interchange specification. So JSON Schema fits and Open API does not.

(Even then, Open API does advertise itself as JSON Schema compatible. That’s not strictly true today but there’s ongoing work to get there.)

To look at a simple OpenAPI schema, check out World Time API.

Back to the ‘what’ of JSON Schema #

So I need to define a data format (or if you prefer, a message or payload format) so that two or more systems can agree that the data is either compatible with said schema, or not compatible.

What are the options? (spoiler: JSON Schema is a pretty good option!)

XML a.k.a. ‘angle brackets’ #

Back in the old days (’naught-ies’ and twenty-teens) this would have been done using an XML Schema Definition (XSD) document. But in the 2020s JavaScript rules and JSON is the lingua franca of the computer systems everyone, so JSON it is.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with XML, but it is pretty verbose, and given that JSON Schema basically is JSON with some rules, it’s generally a lot less effort than ‘parsing angle brackets’.

But not so fast. Even today there are widespread and viable alternatives.

Protocol Buffers a.k.a C-if-you-squint-a-bit #

Top of mind for me is probably Protocol Buffers.

It’s not like I was doing this hands-on when I was at Google, but I certainly came across *.proto or *.pb files aplenty.

And ‘protos’ are really prevalent as a way to describe highly efficient binary messages payloads in RPC systems. They are strongly typed and take versioning seriously, plus there’s support for composition once you start needing reuse.

So why not use protobufs? We’ve had some recent experience on my team working with protobufs in purely client-side code and it just seemed pretty heavy and ’non-obvious’ for the JavaScript or TypeScript environment.

I will say, thought, that the protoc ability to generated JavaScript RPC client libraries from protobuf files is pretty sweet.

ServiceStack for the .NET crowd #

Another aside: I wouldn’t generally start with a .NET toolkit these days. Nothing wrong with .NET at all and most of my heavy programming was with C#. However, most engineers we work with already have a JavaScript compiler on their machine and most do not have .NET. Simple as that.

But…the strong opinion in the entire ServiceStack framework is that of ‘message-first’ development. And if you read even the slightest bit of their ethos around using data transfer objects (DTOs), you quickly see the Martin Fowler influence. And I personally like that influence for the clarity it brings to system integration.

In addition, they have a similar approach to Protocol Buffers for generating client libraries for mutiple languages. So while this is not a good fit for my current team based on using stuff they already use, Service Stack is one to keep an eye on.

Now where was I…?

Right: JSON Schema as a way to define messages/DTOs/data structures.

Learning resources #

- Official JSON Schema getting started guide is predictably good. The sample schemas and how they relate to each other made the URI reference approach really click.

- Opis JSON Schema. This is a PHP implementation so the language itself wasn’t helpful.

However, the documentation is incredible.

For example the

oneOfsub-schema examples were a real ‘Aha!’ moment for me. - Pydantic JSON Schema code generation. As we’ll see in a minute, this turned out to be the golden ticket for me.

Starting with Python #

JSON itself is incredibly easy to understand. Almost the entire specification is captured in a few syntax diagrams. But that’s a far cry from understanding how to defined entire data models in JSON using a set of schema specification rules. It’s kind of like knowing how to spell words in English, then assuming you should ‘just’ understand the rules to writing a sonnet using the Shakespearean form.

I read the JSON Schema official guide and that got me oriented. But I come more from a strongly typed (C#, Java, Go) background, and more recently Python. So the examples, while helpful, were in the language of JSON Schema.

Because of that learning bias, I needed to start with, say, Python and model the schema using a language that comes naturally to me. With that done, I could then see what resulting JSON Schema would look like if I code-generated the JSON from the Python.

Pydantic #

OK so Python to start. I didn’t have to look far to find a Pythonic library that has strong typing and static type checking: Pydantic.

Here’s what that looks like.

First note the imports.

Pydantic gives us a lot of helpers like conint meaning a ‘constrained integer`.

Think, ‘minimum value’, ‘maximum value’, etc.

pydantic.py

| |

Now, most of this is just straight up Python classes, Pydantic base classes and helpers, and then my specific schema types.

Some highlights:

- I use

SketchBaseto plug in a consistent way to name the output JSON schema types in acamel_case_formatlike a JSON-consumer might expect. Enumsare really easy to define. No need to integer types masquerading as strings.PageCoordinateshows how I ensure that page coordinates are always positive integers.Noteshows the use ofPageCoordinateas a reference type, plus theConfig > schema_extrasto drop an example in there.

All in all I found Pydantic to have a low bar to entry into JSON Schema for someone most comfortable with Python.

Human readable documentation #

schema_docs.py

| |

I just stick this into a Makefile so I can run it for multiple schemas if needed:

Makefile

| |

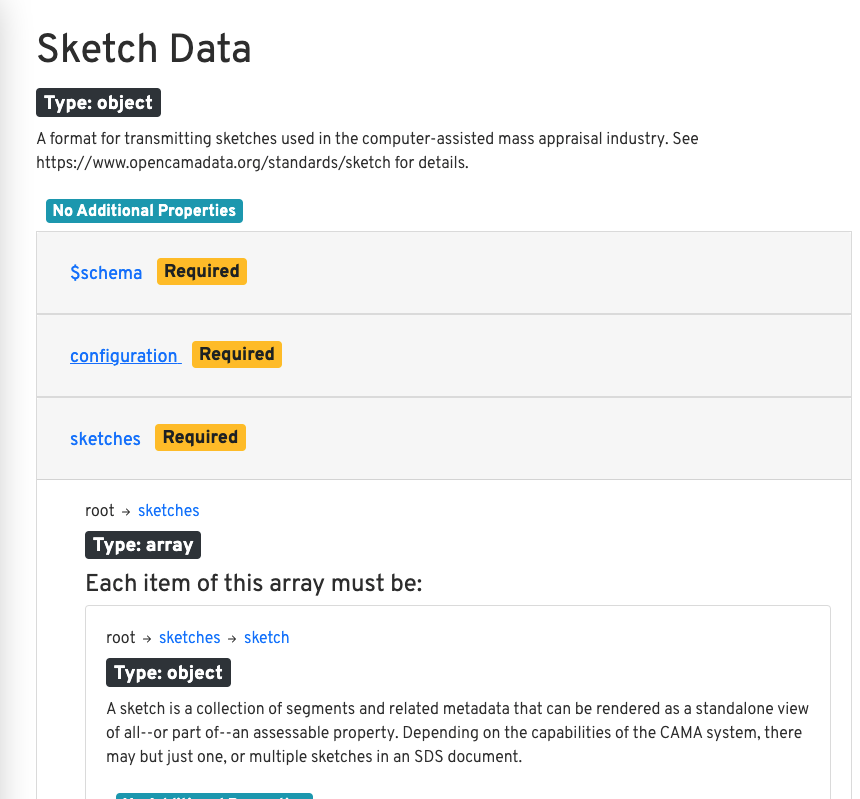

And that gives me a nice way to spit out some HTML to look at:

| |

Tada! We have a nice portable HTML version:

Human readable documentation

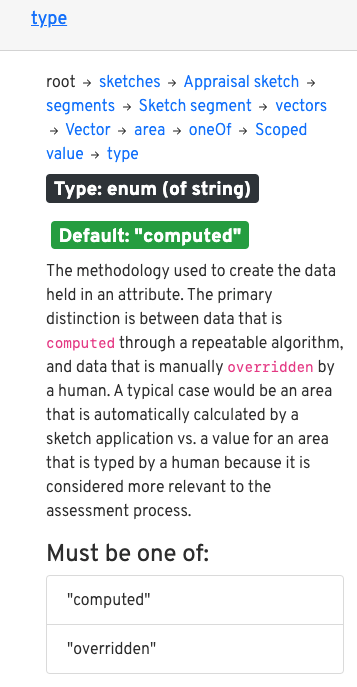

And drilling in to a single type called…type…there’s all the info I might need as a consumer.

One type with detailed description and the enumeration info.

JSON Schema in…JSON Schema #

After a fair amount of munging around with Pydantic I felt like I couldn’t quite express some of the nuances I was reading about in the JSON Schema specs and docs.

For example, getting Python/Pydantic classes just so to produce polymorphic types had me scratching my head.

Specifically, I needed something akin to a set of attribute records associated with a graphic in a sketch (data behind the picture).

And those ‘data columns’ could be one of a subset of valid JSON Schema types.

With that, and a few other needs like proper references between JSON Schemas, I decided to start from scratch by very carefully hand crafting the JSON Schema from scratch, directly in a *.json file.

Cue maddening indentation woes and mismatched curly braces and the usual missing comma shenanigans that comes with JSON and JavaScript in general.

Defining reusable types #

Once I got in the groove there were some nice wins. For example, I could use regular expressions to tightly define how colors should be stored:

| |

And by putting that in the definitions section of the schema I could reuse that throughout. Nice!

And my polymorphic example was pretty easy too. But there’s a fair bit going on in here.

| |

- It’s an array, so zero or more repeating objects representing data behind each graphic in the drawing.

- The items are

objecttypes consisting of akeyand avalue. - The

keymust be a string of _at least 1 character in length. - The value can only be one of a specific set of types.

- Both the

keyand thevalueare required. - You cannot add additional properties onto the key/value pairs.

That last one was really not obvious to me at first. I mean, it’s self evident when you read it, but until I saw the HTML docs it did not quite compute. To whit: in JSON Schema by default you can add any random property you like onto any specified object in the schema. In other words, you can throw random data into your carefully craft JSON Schema and WHOOSH! there goes your easily parse data file.

I quickly got into the habit of setting additionalProperties: false by default just to avoid hiccups like that.

References are DRY #

Taking the definition concept further are including other schemas by reference.

Here is the vector type pointing to a bunch of definitions inline:

| |

But in the config.schema.json file which sits next to the other JSON Schema files on disk we see a different pattern:

| |

Note the inclusion of the local file name then a JSONPath specification for where to find a type by reference using the $ref attribute.

Summary #

So that’s it for my first foray. The schemas are actually public but are obfuscated behind a wonky URL for now. I learned a lot that I didn’t have time to write up yet, like generating strongly typed client libraries and type definitions for TypeScript. But I’ll save that for another day.